Polish Photomontage Between The World Wars

Avant-garde Photomontage in Poland: Utopia and Practice

Photomontage was first used in avant-garde art by the German Dadaists and the Russian Constructivists at the beginning of the 1920s. Both movements viewed the assembling of ready-made photographs as a way of modernising art, or bringing it closer to the life of the times, and of getting in touch with the mass culture then developing. Artists recognised the significant role which the illustrated press was beginning to play in the world following the war and the revolution: it registered the pulse of a rapidly transforming social, political and economic environment, and simultaneously shaped its image for the benefit of the mass reading public. No traditional artistic genre could have achieved such a feat. The Berlin Dadaists used photomontage to enter into a subversive dialogue with the image of contemporariness as created by popular illustrated magazines: a jumble of serious and trivial events from different parts of the world, sensations, curiosities, gossip, fashion trends and commercial advertising - anything, as long as it was new and modern.

For the Russian Constructivists, photomontage became a way of departing from "objectless" art toward a new kind of figurative, socially useful art which was to respond to the challenges involved in the construction of the socialist state and its culture. Whereas the abstract painting practised by Malevich, Rodchenko, and their followers was an attempt to incorporate into art the laws or economy as applied in contemporary industrial production, by simplifying and systematising form, brought down to a set of elementary, standardised, precisely drawn geometrical figures and basic colours, photomontage was seen as the next, and final, stage in the industrialisation of art techniques. (…) The rich output and versatility of Russian artists in the field or photomontage in turn become an example for European Constructivists associated with the political left. Photomontage had many assets: it was avant-garde, technically modern and formally new, ideologically committed to the revolution and the Soviet State, engaged the construction of communist culture, and closely aligned with the printing industry. Moreover, it was universal, and understood by masses with little knowledge of culture. It was a commercial art in line with the system of mass production and mass consumption.

The Poetics of Economy: Photomontages by MieczysŁaw Szczuka

(… ) Photomontages by Mieczysław Szczuka, chief exponent of the Blok group, are an example of International Constructivism. Szczuka was inspired by the art and views of El Lissitzky, who brought revolutionary Soviet art to the West, and by Le Corbusier's L'Esprit Noveau. The writtings of both champions of a new synthesis of art and technology contained calls to subordinate artistic production to the principles of rationalisation, economic organisation, Taylorism and Fordism. (…)

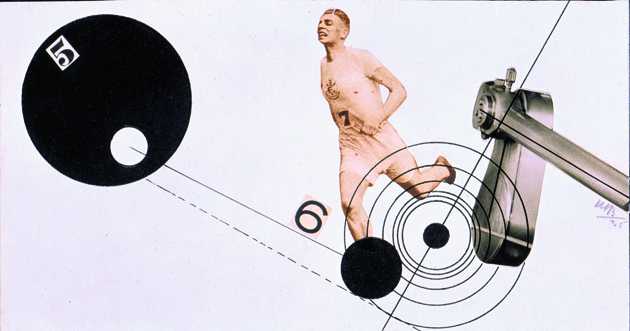

As adherents of this utopian vision, members of the Blok group, Szczuka and Władysław Strzemiński in particular, wanted their art to blaze a trail down which culture would inevitably proceed. Fascinated with the division and co-ordination of labour at Ford factories, in which he saw an ideal model for the functioning of the social organism, Strzemiński developed the doctrine of Unism which was to implement these principles within the structure of a painting. Szczuka opted for the technological modernisation of artistic techniques. He chose photomontage as a new medium of visual communication which corresponded to the standards or an industrialised, mass society far better than painting did. In Szczuka's view, photomontage had the economic advantage over easel painting. The former replaced the obsolescent system of manual production of unique art works marked with the artists individuality with mechanical, precise, unindividualised, quick and inexpensive photographic images designed for mass reproduction and organised according to the rational order of simple, normalised, standardised geometrical figures. Szczuka referred to photomontage as "poetry-art," seeing in it a visual idiom which made it possible to convey meaning just as concisely as contemporary poetry did. This conciseness, which increased efficiency and acceleration of image production was to be accompanied by an increase in impact the image had on the mass public. Photomontages published in Blok's eponymous magazine in 1921 highlighted the development of technology, represented by photographs taken from advertisements for exemplary machines and mechanical vehicles. In league with technology, art was to pursue ideally economical solutions, rigorously visualised in abstract arrangements of basic geometrical forms and perpendicular axes demarcating the framework of the visual construction. These works took on the guise of advertisements for a desired world of disciplined harmony obtaining between industrial machines, the functional appliances produced by them, and the people benefiting from the blessings of technology.

Visual Manipulation: the Political Photomontage

After his death in 1927, Szczuka's brand of agit-prop photomontage was continued by his close associate Teresa Żarnower, who designed campaign posters for left-wing candidates standing for the 1928 parliamentary elections. Within the next two years, photomontages began to appear regularly in left-wing periodicals such as Miesięcznik Literacki, 1930, Kuźnia, Ze świata and Dwutygodnik Ilustrowany, all of which were to a lesser or greater extent controlled by the communist party. The most prolific artists in this field were Mieczysław Berman along with Władysław Daszewski and Stefan Themerson. Most of their photomontages were stylistically indebted either to the propagandist "factography" of Soviet publications, notably the magazine SSSR na stroykye, in which case they praised the achievements of the Soviet Union, or to the virulently grotesque collages by John Heartfield, as was the case with works of political satire aimed against capitalists and Fascists. Montages critical of the American political and economic system illustrated articles discrediting the great myths of the 1920s - the American economy and rational organisation of labour, Taylorism and Fordism - which had fuelled the utopias of the Constructivist avant-garde.

Communist cultural policy promoting crude and politically biased "factography" and opposed to any ideas of artistic autonomy, and the entrenchment of photomontage as a medium of press illustration led to the decline of the technique by the mid-1930s, as the doctrine of Socialist Realism calling for "grand" proletarian art gained ground. As easel painting and "high" art returned to grace among ideologists of communist culture, left-wing artists turned once more to painting. Consequently, attempts were made to bring photomontage into the realm of painting and to fuse the two techniques. Spearheading this movement were Mieczysław Berman, Stanisław Osostowicz, and the proponents of "factorealism" among the Lvov avant-garde. In 1935 when the Communist Internationale adopted the "popular front" doctrine which gave the universal struggle against Fascism priority over the overthrowing of capitalism, left-wing artists (most notably Berman) directed their attentions accordingly. Photomontage dealing with class struggle all but disappeared from the left-wing press. The subject was soon taken up by right-wing nationalists with fascist leanings whose magazines published photomontages addressing social and economic matters, often combining anti-capitalist and anti-Semitic sentiment. Prosto z mostu ran the work of Jan Poliński between 1935 and 1936, while Falanga began publishing anonymous photomontages, as crude as they were explicit, in 1937.

The notions of functional typography and the popular press

The leading theoreticians art modem typography, El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy and Jan Tschichold sought to create a new and "economical" form of visual communication in which photography would, to a large extent, replace the less "effective" written word, and provide, they believed, a maximally clear, precise, explicit and convincing message. It was their influence which, in the late 1920s, led the driving force behind the Constructivist movement in Poland, Władysław Strzemiński, associated with the Praesens group, and later with the a.r., to take an interest in the functional integration art text and illustrative photography and consequently photomontage. Largely thanks to him functional typography was placed at the heart art Polish avant-garde theory and practice in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The programme of Praesens corresponded to the utopian ideals or Unism and the Rytm group and adopted the principles of Taylor and Ford: standardisation, "the mass production of analogous objects for millions art consumers," "maximum convenience with minimum time and effort”, the assembly art ready-made elements as a universal and economical means of manufacture - seeing in them the basis on which all of culture was to be organised. The programme also called for application of those rules to all aspects of creativity with a view to achieving world-wide rationalisation of life. (…)

On the borderline between the political photomontage used in radical left- and right-wing publications and photomontage illustration in popular magazines were the works published by Mieczysław Choynowski in Wiadomości Literackie in 1931-1932. The variety of their subject-matter fit in with the eclectic format of the magazine which had serious journalistic and cultural aspirations while trying to gain a broad readership by avoiding ideological extremes and catering to average tastes. Choynowski's photomontages did not illustrate articles but were printed in a separate column. Some, according to the artist, were lyrical meditations on life, the uncertainty of love, and bemusement by the world. The works had a relatively tree and clear composition based on the contrast of characteristic figures of varied size suspended against an indeterminate white background; sometimes this space would be organised using simple graphic elements such as a circle. The influence of Moholy-Nagy is evident in the choice and positioning of figures, the arrangement of pictorial space and in particular formal devices. Other works touched on specific political issues. Such photomontages were either concerned with the development of Soviet industry, or were anti-American in nature: the latter taking up the ideological and visual stereotypes perpetuated by Berman and others in earlier communist publications.

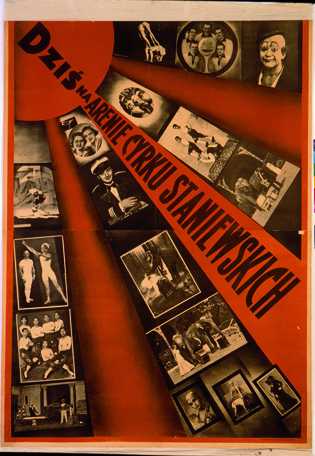

Choynowski was also, along with Marian Walentynowicz, a regular contributor to Naokoło świata magazine. Its use of photomontage was in line with the pre-war concept of photomontage as the static equivalent of cinema. Editing was regarded as the key element organising the structure of films, and contemporary theorists of typography propounded the use of cinematographic effects in illustration. The compositions on the pages of Naokoło świata often combined documentary photographs with film stills (or mock news photos with images made to look like film stills), authentic and staged scenes, depictions of real persons and characters played by actors. As a result, the borderline between reality and fiction became blurred. Documentary and para-documentary photographs used in photomontage served to validate imaginary, usually playful stones, while real-life stones were illustrated with assemblages of film stills in the convention of adventure or romance. In this way, magazines would create an entertaining, half-real, half-fantasy world we would call virtual, drawing their transfixed and disoriented readers into an illusion of reality or producing a sense of detachment by presenting real events as a film of sorts. Readers were supposed to treat such a world seriously one moment and tongue-in-cheek the next - just as they would at the cinema.

Avant-garde under the IKC Masthead:

the Kaleidoscope of Mass Imagination

The understanding of photomontage as a dynamically edited film was shared by Kazimierz Podsadecki and Janusz Maria Brzeski, two of the most productive and possibly most interesting artists practising the technique in 1930s Poland. Both were fascinated with experimental cinema, especially its daring and dynamic editing, which was also found in the best popular productions. They believed that avant-garde film should have a place in mass culture and were dedicated popularising the poetry of editing which they regarded as the essence of contemporary cinematography. Such was the aim of SPAF, the Polish Avant-Garde Film Studio, they established in 1932. (…)

Brzeski claimed that arranging press photographs was the best way to learn modern film editing. SPAF artists thus tried to give the illustrated weeklies they worked for a film-like structure derived from avant-garde aesthetics and "well made" popular movies. The photomontage output of Podsadecki and Brzeski levelled out the differences between the avant-garde and mass culture.

Kazimierz Podsadecki was an artist firmly rooted in the artistic avant-garde, a member or the Praesens group, collaborator of Zwrotnica, highly valued and promoted by Strzemiński with whom he often discussed the issue of photomontage. While he shared to some extent the latter's utopian vision of Constructivism as a means of organising the world rationally, his focus was on the present, as shown in his illustrations for commercial magazines published by the Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny press syndicate. He saw the present not only in terms of progress in technology, engineering and architecture, but also as a vibrant panoply of urban life teeming with dramatic events, swindles, scandals, notorious crimes and love affairs, gaiety and tragedy, spectacular careers, celebrity gossip, fashion and sports news, etc. Such a picture was provided by the weeklies Na szerokim świecie, and Światowid, and Podsadecki's illustrations gave it an adequate visual form, likening the world stage to a dynamically edited film: part newsreel, part comedy, part melodrama, and part thriller.

Podsadecki published his more sophisticated, and usually more interesting, photomontages in Na szerokim świecie. They often took up more space on the page than the accompanying text. The photographs did not make up a separate narrative, merely indicated selected issues, either mentioned in the article or loosely associated with its subject. Many of these were recurring motifs making up an iconography: stacked skyscrapers, money, expressive faces and hands, pointing guns, agitated crowds, etc. Photographs were usually set together to obtain contrasts of scale, perspective and compositional axes, producing vivid visual effects but not giving any insight into the actual relations between individual images. These striking juxtapositions immediately caught the eye; readers were intrigued by appealing subject matter arranged in puzzling ways, their dynamics hinting at a rapid plot which was soon explained by the accompanying text.

In Poland, this type of press photomontage was introduced by Brzeski, who adopted it from the French weekly Vu with which he had co-operated until 1930. After returning to Poland, he began working for the IKC press syndicate as a graphic designer for the pulp crime magazine Tajny Detektyw [Private Eye] (1931-1934). The magazine derived its shock-value from graphic accounts of various crimes and projected an air of grim sensationalism. Cases from police and court files were rewritten in the vein of detective stories. Photomontages blended mug-shots and photographs of real crime scenes and the weapons used with freely chosen photos and film stills which suggestively fleshed in the motives and circumstances of the crime. Seemingly revealing all the particulars of the case as it was followed by the all-seeing lens of the photographer, the magazine couched the story in the standard terms of crime writing. It rehashed the stock repertoire of criminal iconography, perpetuating stereotyped perceptions of the environment in which crime breeds: a world of reckless passion, gambling, alcohol, night clubs, licentious women, suspicious alleyways, etc. Tajny Detektyw's preying on the widespread fascination with crime under the pretext of moralising proved too shocking for the general public, and ultimately resulted in its closure. Brzeski moved on to work as graphic editor of a new IKC weekly, the women's magazine As, established in 1935. In 1933, Brzeski produced a series of a dozen or so photomontages entitled Narodziny robota [The Birth of a Robot]. It showed the ambiguous relations between the human being and technical civilisation, relations as close and erotically charged as they were dangerous and potentially disastrous. (…)

Book Typography and Posters

While the illustrated press was the main vehicle for applied photomontage, the technique was also used in the graphic design of books and posters. The earliest photomontage book covers were produced by Szczuka for the collection of poems by Anatol Stern and Bruno Jasieński, Ziemia na lewo [Earth to the Left] and for Władysław Broniewski's Dymy nad miastem [Smokes over the Town] (1927). Another member of the Blok group, Henryk Stażewski, who sporadically used photomontage, designed the covers for a collection by Lithuanian poet Juozas Tysliava (1925) and a thriller by Jan Brzękowski Bankructwo profesora Muellera [The Bankruptcy of Professor Mueller] (1931). The cover of Anatol Stern's Europa by Teresa Żarnower continued the photomontage illustrations Szczuka had made for the poem. She returned to photomontage during World War II with a series of five poignant, extensive compositions for the book Obrona Warszawy [The Defence of Warsaw], published in 1942 in the USA. The most interesting productions made during the 1930s include the Constructivist-influenced book covers by Berman (Romain Rollanďs Mahátmá Gándhí from 1930 and Opierzona rewolucja [The Fully Fledged Revolution] by Melchior Wańkowicz from 1934). Photomontage was rarely used as book illustration. Besides Żarnower's Defence of Warsaw there were the cover and text illustrations by Władysław Daszewski to Antoni Słonimski's 1928 poem Oko w oko [Eye to Eye]. Berman was also a successful designer of posters in the 1930s: good examples of this body of work include Pocisk. Amunicja do pistoletów automatycznych [The Bullet. Ammunition for Automatic Pistols], which won the Gold Medal at the 1937 International Art and Technology Exhibition in Paris, and Pożyczka Narodowa [National Bonds]. Special attention should be paid to photomontage posters made for the occupational health and safety campaign. These include: Do walki z wypadkami przy pracy [Stop Accidents at work] by Aleksander Rafałowski, Nie zdejmuj przyrządów ochronnych [Keep Your Protective Gear On] by Andrzej Pronaszko, Ostrożnie! Strzeż oczy [Watch Your Eyes] by Karol Kryński, Ręka skaleczona nie może pracować [Injured Hands Can't Work] by Tadeusz Trepkowski.

Surrealist Inspiration

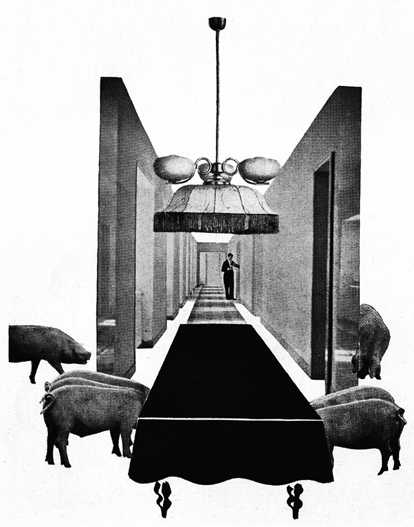

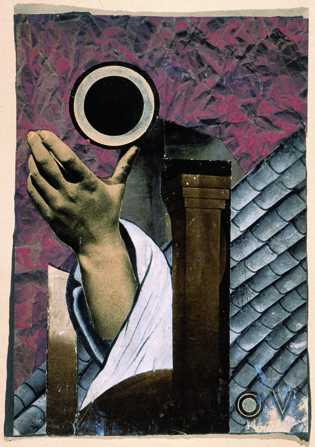

In the early 1930s, purely artistic photomontage was represented by works of artists associated with the Artes group from Lvov. Their superficial version of Surrealism relied on cut-ups to produce surprising combinations of normally incompatible elements. The odd visual associations were to show the unlettered workings of an imagination treed from the confines or rationalism; in this sense Surrealism was in direct opposition to the extremely rational Constructivism. Artes members, however, adopted Surrealist poetics while retaining the constructivist concept of the image as a consciously organised, autonomous and materially concrete structure. They achieved a rapprochement of the two tendencies in highly unorthodox versions, virtually brought down to a set of formal ideas and characteristic motifs. The leading maker of photomontages associated with Artes was Aleksander Krzywobłocki, who began using the technique in 1928. Recurring features of his works include photographs of architectural elements, and hands emerging from unexpected places. However, their most important characteristic is the attempt to blur the recognisability of individual elements and thus bring out the abstract properties of the photographic image, the play of light and shadow, and the textures of barely discernible objects. He gave photography an air of unreality by trimming prints across the contours of photographed objects so as to produce arbitrary figures, leaving only an undefined blurred background, assembling cuttings against the spatial logic of individual frames by, for instance, rotating them 90 or 180 degrees. Using contrast or delicate, soft transitions, Krzywobłocki juxtaposed various surfaces such as walls with different textures of plaster and distribution of light, a sheet of water, a cloudy sky, also using fragments of aerial photographs or snippets of hair. Individual compositions strive towards artistic abstraction to varying degrees. Some manage to evoke the real world through the play of pure form, others are unreal, yet concrete metamorphoses of reality.

Transformation of the female body, anatomical cross-sections, hybrids of people and machines were typical motifs the Surrealist-inspired montages by Otto Hahn (only one reproduction of such works has survived) and Jerzy Janisch (Akt i samochód [The Nude and the Car], Figura z parasolem [The Figure with an Umbrella]. Margit Sielska made collages combining photograph cuttings, fragments of reproductions of paintings, and pieces of coloured paper, highlighting the texture of individual elements.

Photomontage made between the World Wars functioned in a variety of artistic and utilitarian contexts. Brought into a critical dialogue with "high" art by the Dadaists and Constructivists, it was originally intended as a means or visual communication alternative to painting, overturning the paradigm whereby unique works of art provided aesthetic pleasure to the elite within the closed space of museums and galleries detached from the realities of contemporary life. Photomontage was an attempt by avant-garde artists to realise utopian project of a unified, egalitarian culture, levelling out social divisions and antagonisms, and incorporated into the rhythm of the everyday. In practice, however, photomontage became, on the one hand, a tool of offensive and deceitful political propaganda or an illustration of the cheap thrills offered by the tabloids, and on the other, simply one of the many artistic techniques used by painters, engravers and photographers. It became an integral part of modem culture and the stuff of an art on the sidelines of that culture, rather than an agent m the construction of a better world. It could not have been otherwise.

Stanisław Czekalski

Text is edited.

The complete text can be found in

the catalogue printed for the exhibition of the same title.

The exhibition took place from March 3 till April 4, 2003

in Zachęta Państwowa Galeria Sztuki, Warsaw, Poland.

Catalogue ISBN 83 89145 16 2